Introduction

As the world’s oldest continuous civilization, China’s history stretches back more than 5,000 years to the Neolithic time. Recent advances in Archeologic Science in China have also shone a light on the culture as it has never. As a civilization, jade has always played an important part ever since the dawn of Chinese history, revered as mysterious and precious. Carvers often express their religious beliefs in an artistic form, to adorn kings, queens, nobles, and influential leaders of the society and buried with them at their death. Since jadeite only came into China after the Ming Dynasty, Jade in China before the Ming Dynasty was always nephrite. As a mineral, nephrite can last thousands of years and are better preserved as an artifact than wood and may even better than clay wares and metal. To look into the society of the time, especially into their religious beliefs, is no better than through the buried nephrite. However, buried nephrite of Chinese antiquity is notorious with rampant forgeries to the point that fakes and genuine buried nephrites may not be distinguishable. Unfortunately, even the Chinese government may not be helpful in this regard. On the internet, imageries are near 100% fake jades. Self-proclaimed reference books post fake jade photos. Of the three Chinese Neolithic jade cultures, Hongshan (4700-2900 BC), Lingjiatan (3750-3000 BC), and Liangzhu (3400-2250 BC), Hongshan should be considered the earliest jade culture. But Hongshan jade is also the most chaotic. With so many fake Hongshan jade flooded the market, ironically, even the forgery carvers themselves may not have seen an authentic piece of Hongshan jade. As a result, fake Hongshan jade may not be a copy of the original, but merely something out of the fake jade carver’s imaginary. The tragic consequence is people, including the Chinese themselves, are unable to see the real face of the Chinese civilization.

The Hongshan archeology sites were discovered in the early 1920s. Between 1983 and 2003, the Liaoning Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology undertook a series of extensive excavations of the sites. Other than many significant archeologic artifacts, 100 pieces of jade were obtained. These 100 pieces also include those damaged and incomplete. Some scholars estimate that 90% of the jade artifacts were removed illegally before the official excavations. But if you take 10% is 100 pieces, the total number of Hongshan jade is only 1000. Compare that with the hundreds of thousands and may even be a million fake Hongshan jade on the market today, one can easily see genuine Hongshan jade is a rarity. Hongshan culture, despite the fact being Neolithic, obtained high artistic levels in their jade carvings, even in today’s standard. Replacing such artistic achievement by the distasteful jade carvings of today distort not only the origin of the Chinese culture but also disrespectful for the cultural heritage of their ancestors.

Because of the rampant forgery, it is imperative that the Hongshan jade pieces presented here must be genuine, and the proof of such has to be in the authentication. Traditional authentication is comparing the jade piece to a known unearth relic. However, because the Hongshan jade obtained from the excavation is only 10%, it cannot be representative, and comparing the jade piece to the excavated ones is meaningless. Authentication must rely on the recognition of tool marks and color change on the jade surface. It is especially important to the color change that results from the weathering process of the mineral nephrite (see the article Chemical Weathering on this web site). The method of authentication will be presented. Only with some certainty that the jade pieces are genuine, that looking through them into the art and beliefs of the Hongshan society 5,000 years ago can make sense.

Hongshan Conspectus

Hongshan culture (4700BCE-2900BCE) was one of the Neolithic cultures in North-Eastern China, stretching north from southwestern Inner Mongolia, south to northern Heibei, and East to Liaoning. The name that applies to this vast area includes over one thousand village archeology sites of the same culture. In 1908 the Japanese archeologist Ryuzo Torii first discovered the site. Limited excavations were carried out by French and Japanese areological teams in the 1930s. It was not until 1983 to 2003 that the Liaoning Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology undertook a series of extensive excavations. It becomes known that the Hongshan culture was based on Xinglongwa Culture and Zhaobaogou Culture and was the most advanced culture in northeast China of the time, advanced from hunting and gathering into farming communities. Stone tools were used for hunting, fishing, farming, pottery making, as well as for jade carving. The most significant finds were a goddess temple with a life-size painted head of the goddess, round sacrificial altars, and square stone tombs. Within the graves, a variety of jade articles were found as sole buried objects with no other artifacts such as pottery or stone tools. Jade, as the only buried objects, indicated that they were objects of religious belief rather than objects of earthly value. Hongshan produced jade objects of varies form. Most notably were the C-dragons, pig dragons, beast in human form, animals, insects, and birds, with the more abstract form the hooked cloud plaque. Despite being a Neolithic culture, Hongshan produced many of the jade pieces with high artistic levels comparable even in today’s standard.

Hongshan culture had developed highly sophisticated pottery made with metal molds from fine red clay decorated with black geometric patterns. Pottery was mainly bowls, plates, pots, and cups for daily use. Among the pottery was a bottomless round tube that could not carry food and drinks, making it an unlikely utensil object (Figure 1). These tubes were found in large tombs lining the sides of the grave. The

geometric black paint pattern on the tubs was also unique, unlike those on other pottery, indicating that these tubes most likely had a religious function. Six female clay figurines in pregnancy were also found, linking the culture to fertility worship (Figure 2). Such

religious beliefs in pregnancy and the bottomless tube, also are reflected firmly in many Hongshan jade pieces, as we shall see later.

Authentication of the Hongshan Jade

The most notable and well known about Hongshan culture is its jade, with the C-dragon and the pig dragon as the most representative. Others are animal forms of beast, birds, tortoise, the horseshoes, and the hook cloud plaques. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson’s paper “Jades of the Hongshan culture: the dragon and fertility cult worship.” https://www.persee.fr/doc/arasi_0004-3958_1991_num_46_1_1303 listed all the jade pieces from the official excavation with drawings and can be regarded as the most reliable reference source in the study of the Hongshan jades. These jades have a beauty of its own and can truly represent the culture on its own right. Unfortunately, because 90% of the Hongshan jades were lost before the excavation, the excavated jades can only give a glimpse of its true nature.

Most of the Hongshan jades are small, ranging from 3 cm to 8cm in length. Larger pieces can be as long as 18cm, with some hook cloud plaque as long as 28cm. The size of the Hongshan jades is similar to Chinese jades from other periods before the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1912 AD). To understand this size uniformity, one has first to look at Hetian. Jade rough or raw jade has been coming from Hetian since the Shang Dynasty (1600 BCE – 1046 BCE). Hetian jades are from pebbles in the stream and small boulders from riverbeds. These pebbles and boulders are small in size, and hence the size of the jade rough limited the size of the jade pieces carved. It was not until the early Qing Dynasty that jade veins in the mountain were mined. For sure, Hongshan jade rough did not come from Hetian. It is also highly unlikely that Hongshan people were able to mine jade veins in the mountain. The size of the Hongshan jade pieces indicates that the source of the jade rough should be similar and was also from streams and riverbeds. For such reason, any Hongshan jade bigger than 30cm should be highly suspicious for modern day forgery. Traditionally comparing the shape and style of the carving of a jade piece to a known unearthed piece is the first step of authentication. However, since the majority of the Hongshan jades are lost, the unearth pieces may not represent the culture. Authentication here will look at tool marks and color change on the jade surface. Such color change is the result of secondary products formation from chemical weathering when the jade was buried.

Tool marks identification

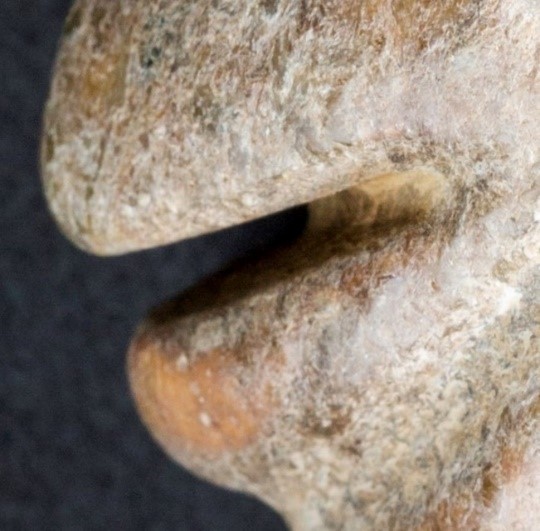

The most important thing about tool marks on the Hongshan jades is not the tool marks, but rather the lack of it. In 2004 the British Museum published a paper “The identification of carving techniques on Chinese jade, Margaret Sax, Nigel D. Meek, Carol Michaelson, Andrew P. Middleton; Journal of Archaeological Science 31 (2004) 1413-1428”. The authors examined six pieces of Chinese jades that belonged to the British Museum for carving tool marks. Positive molds were made for any tool marks found under a microscope. The molds were then examined under an electron microscope to determine the carving technique of the jades. Of the six pieces, one was a Hongshan bird. After a thorough examination, the only tool mark found on the Hongshan bird was line cutting marks inside the drill holes at the top of where the two holes met. The lack of tool marks on the surface probably was due to the polishing at the time of the carving and the subsequent weathering effects on the jade surface, as the authors explained. If we look at the Hongshan jade, the technique employed by the Hongshan jade carvers was principally grinding and polishing. To make the feature to be delineated to stand out, the material around the feature was ground down to make shallow and wide grooves, as seen on the facial feature of an eye and nose (Figure 3 and Figure 6), and around hand and arm (Figure 4). Thin carve in lines was seldom used except on pig dragons, especially on the larger ones. Such a technique of grinding and polishing was done with

abrasive, which results in a smooth surface with no tool marks. A good example is the bird figure in figure 6. Another carving technique used was line cutting, also with the help of abrasive, as demonstrated on the mouth (Fig. 5). The cutting on the mouth is straight, but the flexibility of the line results in the floor of the mouth not leveled.

Drill holes are significant features of the Hongshan jades. Most of the smaller pieces, 8 cm or smaller, have drill holes. Larger pieces bigger than 14 cm, as a rule, do not have drill holes. Such finding means that smaller pieces were used as hanging pieces to adorn the body, whereas larger pieces were statues. There are two types of drill holes. One type is direct through and through round holes from one side to the other, as seen on the bird behind the eyes (Figure 6). The other type is a two communicating holes

diagonally drilled from the same surface (Figure 7). These types of drill holes are often

referred to as the ox nose holes and are exclusively associated with the Hongshan jades. The resemblance to an ox nose can be easily seen with the extension of the part outside of the opening of the hole. Drilling such holes requires the drill placed at an angle on the jade surface. The position of the drill is the cause of the hole widening into an ox nose shape. In many of these diagonally drilled holes, like those in figure 7, such assertion is accurate. But in some ox nose holes, like the one on the C-dragons and hook cloud plaques, may have a different reason. These holes are not diagonally drilled and the holes are not on the same surface. These are through and through holes from one side to the other side, and yet they all have the extension ox nose part (Figures 8a, b, figure 9a, b, and figure10). Drilling a through and through hole, the drill is placed at ninety degrees

to the jade surface. The placement of the drill in this position will not cause the formation of the ox nose part (see the round through and through hole in figure 6). The ox nose part of the holes on the C-dragon and the hook cloud plaque must be an add on to the through and through holes, placed intentionally. Notice the ox nose parts are also pointing at different directions. On figure 8a, b, C-dragon, the directions are upward and downward. On the C-dragon in figure 9a, b, the directions are forward and backward. On

figure 10, hook cloud plaque, the ox nose parts are pointing upward to either side. Notice

the pig dragon on the back of the C-dragon in figure 8a, b, the round hole on it does not have the ox nose part. The ox nose parts are only on the C-dragon. A C-dragon and a hook cloud plaque without the ox nose on the round through and through holes should be highly suspicious for modern day forgery.

The Hongshan culture eventually disappeared from Chinese history, and with it the same surface diagonally drilled holes. All subsequent hanging holes on Chinese jades were the round through and through type. It was not until the middle of the 20th century when mass-produced fake Hongshan jades came into the market that these same surface diagonally drilled holes returned to China. The same surface diagonally drilled holes do not necessarily have the ox nose part (Figure 11). This type of drilled holes was

used extensively on the netsukes in Japan (figure 12a and b), before they came back to

China. No one knows when and by whom the netsukes were created. The earliest netsukes are of the late eighteenth century. The fact that there is no drill hole in the world drilled on the same surface other than on Hongshan jades, raises the question of the relationship between the netsuke and the Hongshan jades. The Japanese netsukes have a high resemblance to the small size Hongshan jades. Adding to that the circumstance around the Hongshan site discovery was also interesting. The Hongshan archeologic site was first discovered in 1908 by the Japanese archeologist Ryuzio Torii. He was at that time a teacher in Mongolia for the royal family. For no known reason, Ryuzio Torii went hundreds of miles straight to the Hongshan site, without searching as if he knew where the site was and became the first person who discovered the Hongshan site. No doubt netsukes have the origin and root in Japan. But evidence points to a likely scenario that some Hongshan jades came into Japan during the late eighteen century and greatly influenced the netsukes development.

Not all Hongshan jades are lack of tool mark. The most apparent drill mark left behind a Hongshan jade is on this drill hole (Figure 13). The hole is not thoroughly

through and is on a 17.5 cm X 15.75 cm hook cloud plaque behind the face of a beast (figure 14). On the side of the drill hole are circular, irregular, and shallow marks, a sign

that it was drilled with a hand drill with abrasive, as in contrast to marks made with modern drills that are deep and regular, similar to marks left behind from a screw. Also, notice that the edge of the bottom of the drill hole is deeper than the center. This indicates that the drilling was done with a center hollow drill, and hence the pressure was applied only on the edge at the part of the drill where it was solid. Abrasive was used and because only the solid part of the drill was effective, drilling was only at the edge of the hole, at the solid part of the drill. As the drill went down the side of the drill hole, the hollow drill left a core in the center. The core was then removed by chipping, and the bottom smoothed. Speculation has been that the hollow drill was a piece of bamboo. But the softness of the bamboo makes it unlikely to be the drill for the much harder nephrite surface. The diameter of many of these drill holes are small, often 3 – 4 mm. To drill such a small size hole, a piece of bamboo of similar diameter must be used. Bamboo of this size will not be able to withstand the constant twisting during the drilling. The more likely candidate for such a drill is a piece of an animal long bone, like an arm or leg bone. Bone has a hardness of 5 on the Mohs scale, like that of iron, making it a much suitable tool than bamboo. The readily available bone is also known used as a tool since the Paleolithic time in China.

It has long known that Long drill holes in Neolithic China tend to taper to the center and are drilled from both sides. The reason for such a tapering effect is because only one piece of bone was used as a drill for half of the hole. During the drilling, friction and rubbing of the drill against the side wall decreased the diameter of the bone drill as it went down. As a result, the hole tapered towards the center. Because all animal long bones are hollow in the center, the drilling creates a central core in the center of the drill hole. The small diameter of the drill hole requires a small animal bone with small long bone diameter. Since the diameter of the bone was relative to the length and as the drill hole tends to have a small diameter, the piece of bone used also tends to be short. For the longer drill hole, it was necessary to drill from the other side. The same tapering effect to the center will result. When the two sides met in the middle, the core was released and dropped out. Due to the slight imperfection of alignment, it always left behind a small notch in the middle of the drill hole. As animal long bones came in pair, a similar diameter size and length bone drill could be easily obtained for drilling from the other side. Drilling in such a way was the most efficient with the least effort.

Identifying modern tool marks on the jade surface is one way to identify forgeries. Recognizing toll marks of the period, together with recognizing changes on the jade surface resulting from chemical weathering, are essential to separate the genuine from the fake buried nephrite.

Chemical weathering effects

For centuries people know that Chines buried nephrites underwent a color change from its original natural state to a greyish, brownish, reddish, and may even be blackish discoloration. Such changes are taken for granted, and no one knows why, and no one has asked any question of what causes such a change. However, simulating such a change of color on the nephrite surface is the principle way to make forgeries. Therefore, recognizing the actual natural color change and knowing the reason for such change on the jade surface is crucial to identify the fakes from the genuine. The buried nephrite color change comes from the secondary products produced from the chemical weathering process when the nephrites were buried. All minerals and rocks undergo the weathering process in a natural environment. There are two types of weathering, physical weathering from wind and water erosion, expansion and contraction from frost and snow, and invasion from animal and plant when rocks and minerals are above ground. Chemical Weathering is a chemical process of the interaction of minerals and water when they encounter underground. Chinese nephrites were buried in graves and tombs, some like Hongshan jades for over five thousand years. Secondary products from the weathering process form inside the micropores and microcracks of the nephrite. Because there is a limit to how deep water can penetrate the nephrite surface, as more secondary products are formed with time, the limitation of how deep it can go into the nephrite forces the secondary products overflow from the micropores and microcracks onto the jade surface. As the secondary chemical products spill onto the surface, they form crystals with specific color different from the nephrite. Because all the secondary products have their own color, the crystallization of such products on the jade surface, together with the secondary products form inside the micropore and microcracks of the nephrite, is the reason for the color change on the buried nephrite. The changes in the nephrite only occur on the topical 0.1 – 0.2 mm. The limitation of the changes to only such a thin layer is the reason why using spectroscopy and x-ray diffraction in the laboratory to test the buried nephrite only gives the answer that it is nephrite and does not verify the chemical weathering effect on the surface. The chemical weathering effect can be easily observed under a 40X magnification stereo microscope. It must be emphasized that none of these changes has been confirmed scientifically. All are based on the correlation between observation and reference from Chemical Weathering literature. (See the Nephrite Fundamental and Chemical Weathering Blogs on this site). Hopefully scientific confirmations will eventually come. But the observation of the changes is accurate enough to identify genuine buried nephrites from forgeries as we look into the Hongshan jades from this perspective.

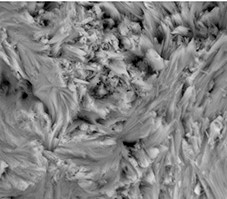

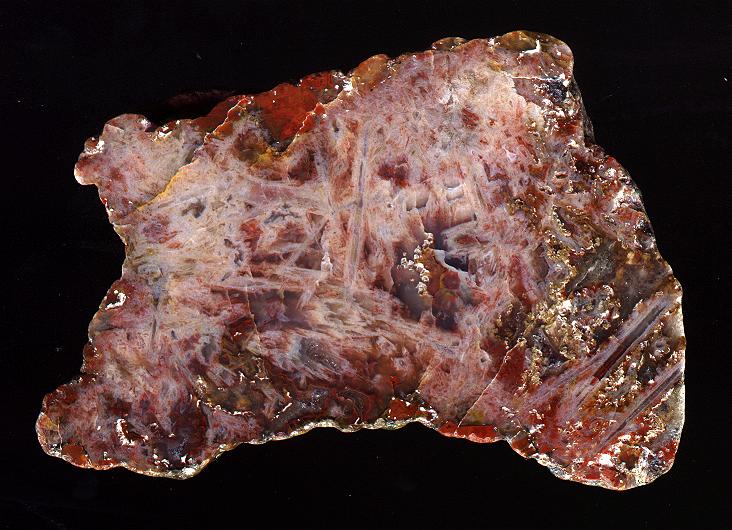

Nephrite can be considered as a mineral even though it composes of Actinolite and Tremolite. Chemically It is a calcium, magnesium, and iron-rich silicate belonging to the amphibole group and has a needle-like fibrous crystal structure (Figure 15). Iron is what gives color to Nephrite. Tremolite is rich in magnesium and therefore

white, and Actinolite is rich in iron and therefore has the color of green, yellow, brown, and even black. The proportion of Tremolite and Actinolite in Nephrite determines the color of the nephrite. Today any Nephrite containing more than eighty percent of Tremolite is considered Hetian mutton fat jade regardless of its origin. Within the nephrite, there are micropores and micro-cracks seen only under an electron microscope (Figure 16). Such micropores and micro-cracks play a crucial role in

Chemical Weathering and color change on the jade surface, as we shall see.

Igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks form the crust of the earth. Igneous and metamorphic rocks form in the earth mantle under high temperature and pressure. As they move into the low temperature and low-pressure crust, they become unstable. Physical weathering first breaks up rocks into smaller boulders and pebbles. Chemical weathering eventually reduces them into more stable minerals, releasing cations, forming clay. Clay minerals, together with sand, hummus, and water, become soil. Without weathering there will be no soil and without soil, there will be no plant and no animal life. Life as we know it will not be possible, emphasizing the importance of weathering in nature. Water is the most crucial element of weathering. As a result, weathering is a slower process in cold and arid areas and less pronounced than in wet and hot regions. Within the same area, weathering effects can be different on the same rocks and minerals due to differences in water flow, and the surrounding environment of the rocks. Even on the same pebble, varying degrees of weathering can be observed in different parts due to the influence of water flow. All of these are important to remember when observing the chemical weathering effect on the buried nephrite. The differences in location of the buried site, over hundreds or thousands of years in the change of water flow, periods of wet and dry weather change, and shifting of soil can all influence the weathering effect observed on the buried nephrites, and are important to consider when looking at the weathering effect.

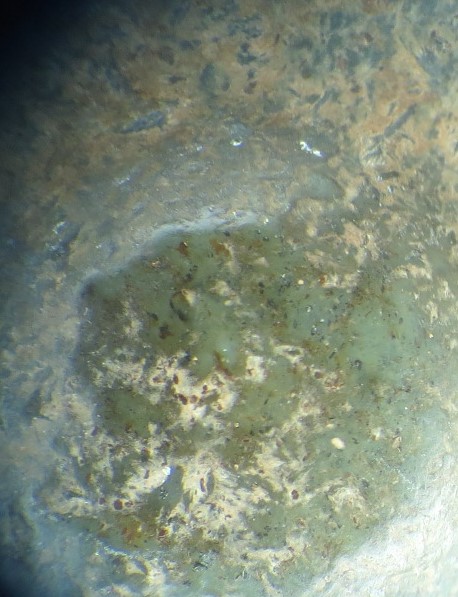

Dissolution and leeching are the initial steps of Chemical Weathering. In nephrite, calcium, magnesium, and potassium leach out, flowed with water, and eventually lost to the sea, contributing to the salinity of the seawater. Silicate also leeches out, but in proportion to a lesser extent. The loss of cations leads to crystal structure change and amorphous silicate forms. Often the whitish-grey amorphous silicate appears on the nephrite surface is mistaken as calcium (Figure 17). On many fake buried

nephrites white powder is randomly placed on the surface to simulate the amorphous silicate. Notice in figure 17, the distribution of the amorphous silicate has a pattern. During the jade carving, a large amount of fine nephrite granules was produced and left around the cut lines, in groves, depressions, and drill holes, places where polishing was unlikely to reach. Such areas also tended to retain water. The dissolution of these fine granules into amorphous silicate resulted in an appearance as if the amorphous silicate was outlining the lines and groves, as shown in figure 17. It is also the reason why large amounts of such whitish-grey amorphous silicate are often found inside drill holes obscuring tool marks.

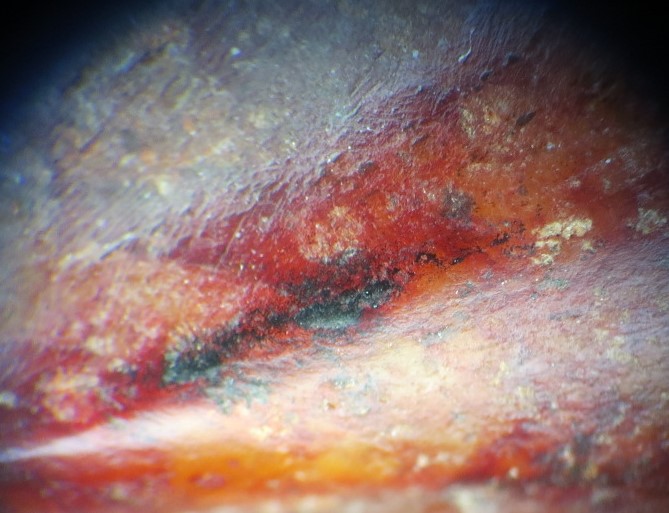

Leeching and dissolution enlarge micropores and microcracks. Hydrolysis and oxidation also take place, and secondary products form. Nephrite, as a member of the amphibole group, forms clay minerals Smectite and Kaolinite, and iron oxides Hematite and Goethite. The clay minerals have a white to greyish, yellowish color. The iron oxides Hematite has a deep red to brownish red color but also can be dark grey. The other iron oxide Goethite can be yellow, red, deep brown, and can also be black. The formation of the secondary products on the jade surface is the basis of color change on buried nephrites. As hydrolysis and oxidation require water, water determines all changes seen on the nephrite, and since the penetration of water into the nephrite surface is limited, only 100 to 150 angstroms from scientific studies, changes are only limited to an extremely thin topical layer. Secondary products first form in the micropores and microcracks as a ferruginous gel-like substance. Depending on the secondary products formed, the buried nephrite color starts to change into the secondary product color in the micropores and microcracks. At first the nephrite loses its luster, and as more products form, the color begins to change as in the Song frog in figure 18. Due to the lack of water penetration, as more secondary products formed,

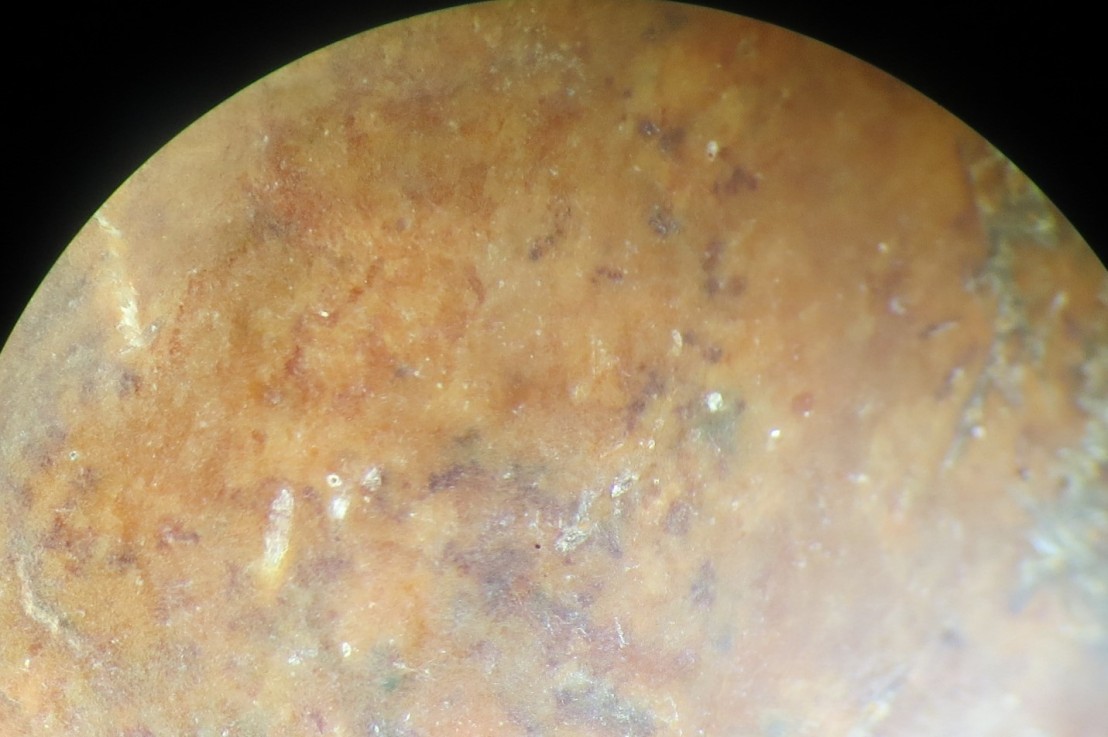

micropores and microcracks behave as they are plugged. Continue formation of the secondary products results in the spilling of the ferruginous gel onto the surface of the nephrite forming a crust, and eventually crystallize. Similar changes also are seen on the nephrite pebbles found in streams. Many of the secondary products developed on the surface may have washed away by the water stream. But iron oxides Hematite and Goethite can crystalize, and a reddish, yellowish skin can form on the surface together with greyish clay phyllosilicate (Figure 19).

Throughout Chinese history, collectors consider there are two types of buried nephrites, those newly unearthed, and those in collectors’ hands for generations. Those newly unearthed retain all the chemical weathering effect. Those that have been in collector’s hand underwent surface cleansing. Chinese collectors habitually rub and may even scrap the jade surface to clean what they consider dirt in an attempt to return the jade to its pre buried color. Many hundreds of years of such rubbing and cleaning results in the removal of the crust made of secondary products, exposing the jade surface with the secondary products still in the micropores and microcracks. Figure 20 is a Han (221 -206 BC) beast that has been in collectors’ hands for hundreds of years. Frequent

rubbing, scraping, and cleaning results in the removal of the secondary products, exposing the jade surface. Figure 21 shows the Han beast surface under a 40X stereotactic microscope. During the dissolution and leaching phase, due to the loss of substance, the surface micropores enlarge, and eventually, they coalesce forming an elongated shallow pit as if the jade has lost a small piece of skin as shown in figure 21. A brownish protonation layer where the chemical reaction took place, form at the bottom

of the pit. The protonation layer is only a few atoms thick and cannot be removed with ultrasound cleaning. The red arrows point to two thin silvery lines with a metallic shine. Such silvery lines are frequently seen on the buried nephrite surface. Most of them are in single file straight lines, with some seen at the edge of the crust edge. Because the angle of reflection of such lines is not ninety degrees, to see these lines, one must hold the jade piece to put it into the microscope focus, tilting the surface to look at the surface at different angles. The nature of these metallic lines is not clear. But in some, they seem to be formed by tiny metallic granules. Looking under the microscope obliquely by tilting the jade is also the best way to appreciate the thickness of the crust and the crystal formation of the secondary products on the jade surface. Notice there are phyllosilicate crystals of the clay mineral remain on the right side of figure 21, despite hundreds of years of rubbing and cleaning by many generations of owners.

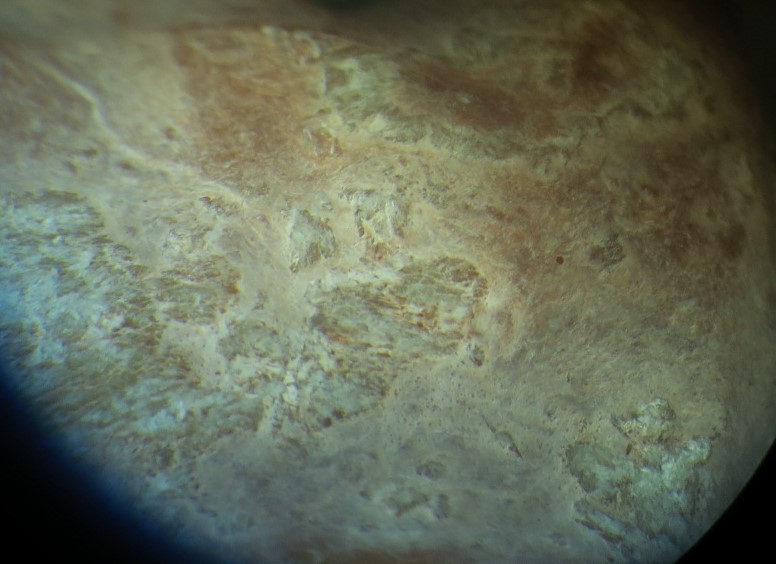

Most of the metallic lines are silver. Less often seen are the golden yellow metallic lines. Figure 22 is a Hongshan zoomorphic. Under the microscope (Figure 23a),

the edge of a semitransparent, smooth ferruginous crust can be seen at the center with golden-yellow granules forming a line (in red circle). Below the red circle are phyllosilicate crystals of clay mineral formation. The greyish-white material has a look of irregular thicken plaque made up of sheet-like crystal of the phyllosilicate. All of these are on top of a darkish red iron oxide that encases the whole beast zoomorphic, giving the beast a reddish look (Figure 23b). In figure 23b under a 24X stereo microscope, at an oblique view, the secondary product of iron oxide, likely Hematite, can be view covering

the surface of the zoomorphic beast. The iron oxide covering is what gives the apparent color change of the nephrite. In another view of the zoomorphic beast in figure 22, greyish white phyllosilicate clay crystals are on top of the iron oxide crystals (Figure 23c). Notice also the straight silvery metal line indicated by the red arrow. The appearance of

the buried nephrite is the result of the secondary products from Chemical Weathering accumulating on the jade surface. The iron oxide encasing with phyllosilicate crystal formation on top is also illustrated by the Neolithic disc on the front cover of Jessica Rawson’s book. “Chinese Jade, From the Neolithic to the Qing.”

Silvery metallic granules are often in a line. Those on the Hongshan zoomorphic on top of a worm (Figure 24) are in a group. Figure 25 is the magnified view of the jade surface with a group of metallic granules marked in a red circle. Around these

granules are the sheet-like phyllosilicate crystals of the clay minerals. Viewing buried nephrite with naked eyes can be deceptive. The surface on the C-dragon – pig dragon in figure 26 appears damaged on observation. Such an effect is often simulated by fake jade makers with sandblasting, and color manipulation by driving in dye and paint with heat

and Ph, to obtain such appearance. Under the microscope, it becomes evident that such appearance is not damaged but is due to the accumulation of secondary weathering products on the surface, entirely different from that on the fake jades. In other words, weathering changes on the buried nephrites cannot be simulated, and recognizing such changes is a good tool for authentication.

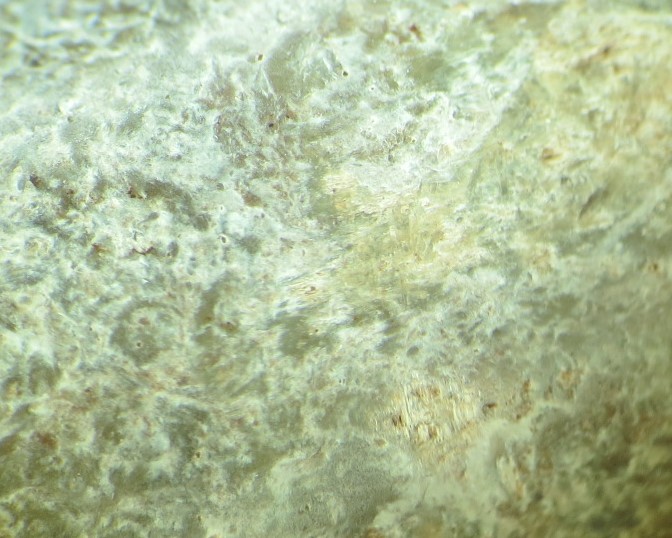

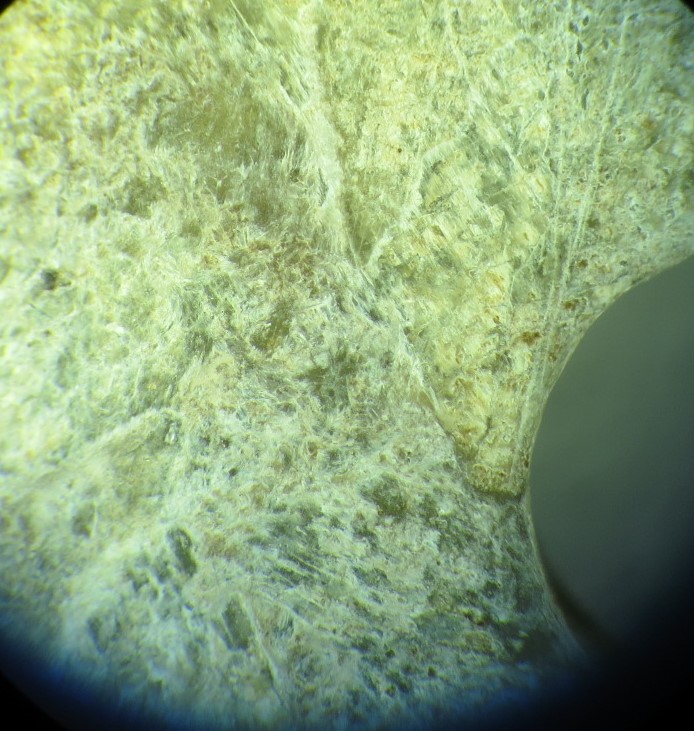

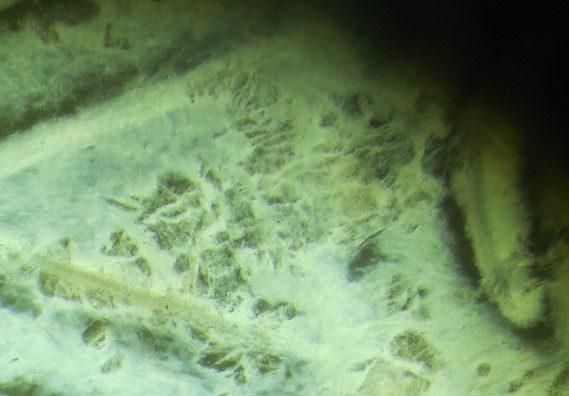

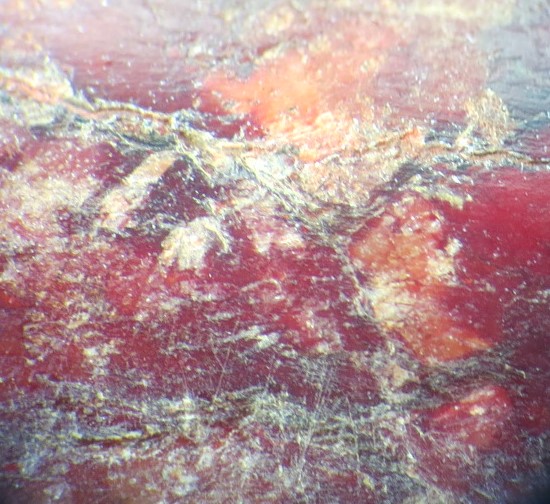

As a group, Hongshan jades are buried the longest, for 5,000 to 6,000 years. The long burial time results in a large amount of secondary product accumulation on the surface, and hence with the most pronounce chemical weathering effects. Two clay minerals are formed, Smectite and Kaolinite. Clay minerals are phyllosilicates that form sheet-like crystals, and the accumulation of the crystals is what gives the irregular appearance of the surface. Figure 27 is the magnification of the C-dragon – pig dragon surface. Notice the thicking of the greyish-white crystals is what gives the appearance of

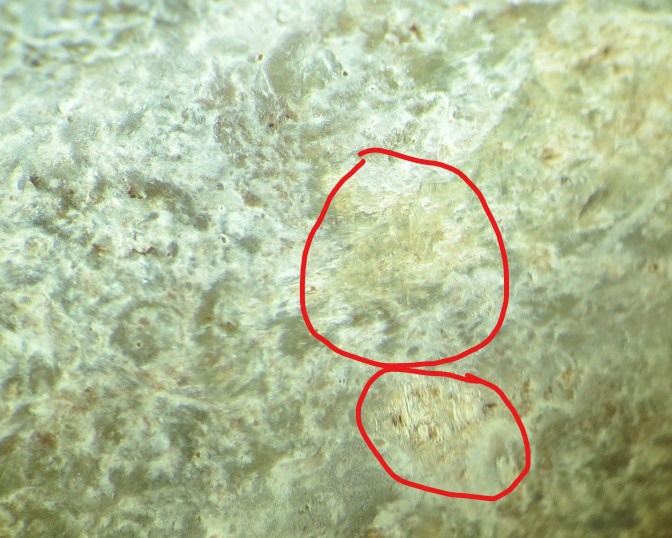

an irregular surface. Crystals have structure as noted on the right side of the magnified field, as opposed to the fake jades with white powder forming a thick paste. As the phyllosilicates come from a ferruginous gel, the presence of iron oxides gives the color a brownish tint. Variation of crystal form exits in different parts of the same jade piece due to many sub members of the clay minerals form various shapes of crystal. Smectite has 22 members, and Kaolinite has several. Figure 28 is the magnification of a different part of the C-dragon – pig dragon. Notice the difference of the crystal formation, more elongated and string-like than in figure 27. Chemical weathering is a very complicated

process, and much of it is still unknown. Various chemical reactions and numerous mineral formations result in different locations of the same piece of jade with different effects seen under a microscope. Simulation on fake jades is uniform throughout. Understanding this will significantly help in forgery identification.

Very few minerals give out an odor, and clay mineral is one of them, giving out the smell associated with soil. Chinese antique jades’ collectors have long known that buried nephritis has a scent that they referred to as tomb smell. This scent comes from the clay minerals formed from the chemical weathering process. Accumulation of clay mineral from the chemical weathering process on the jade surface increases with time, and only when enough clay minerals form on the jade surface that the buried nephrites can give out such odor. As a result, such odor comes only from jades Han or older, and the older the jade, the stronger the smell.

Crystals on the jade surface formed from the chemical weathering can have different shapes and forms. Figure 28a, also a magnification of the C-dragon – pig dragon, shows a patch of tile shape crystal within the two red circles. Such often found in

isolated patches crystals likely is pseudomorph formation. Pseudomorphs are minerals with chemical substances of one kind and a mineral crystal form of another kind as it alternates from one mineral to another. Pseudomorphs, often referred to as Raised Relief on Chinese nephrites, form in the geochemical world, when conditions become suitable. An example of natural pseudomorph is in figure 29, a Limonite pseudomorph after Siderite. Nephrites, when buried, return to the geochemical world, and pseudomorphs

form. As pseudomorphs take time to develop, they only occur on nephrites Han or older. When they occur, they are multiple. Figure 30 shows a late Zhou to Qin (201-206 AD). Jade man with numerous nodules on the body. Under microscopic magnification, these

nodules are formed by tile like crystals (Figure 31). Raised relief or pseudomorphs are

more often found in Hongshan jades for the apparent reason of the Hongshan jades’ longest burial time. Figure 32 is a Hongshan zoomorphic beast with multiple raised relief

on its body. Under the microscope reveals the similarity of the tile like crystal structure of these nodules to those in figure 31 (Figure 33). One difference between the two is that

there are metallic granules found on the nodules on the zoomorphic beast (Figure 33a), whereas metallic granules are not found on the jade man. Such a difference may indicate

that the chemical composition of the nodules is different between the zoomorphic beast and the jade man and that iron oxide are present in the secondary products in the zoomorphic beast giving the zoomorphic beast a reddish color. Pseudomorphs alter from the original mineral to a new mineral depending on the environmental influence. Raised relief on one jade surface may be a different mineral from raised relief on another jade surface. Figure 34 is a natural Agate pseudomorph. Notice the similarity of the crystal

arrangement between the Agate pseudomorph and those on the jade man (figure 30 and 31), and on the Hongshan zoomorphic (Figure 32 and 33). Figure 35 is another Hongshan

zoomorphic beast. The pseudomorph on this zoomorphic beast (Figure 36) is completely

different from those on the jade man and the zoomorphic beast in figure 32 and more like the Limonite pseudomorph in figure 29. The different types of pseudomorph are further demonstrated in figure 37, another Hongshan zoomorphic. The pseudomorphs

on its body all have a Smoke Quartz appearance (Figure 38). All of these say that the

raised relief on the buried nephrite may have different chemical compositions. There is one essential consideration when comparing pseudomorphs on the jade surface to the naturally occurring ones. The naturally occurring pseudomorphs are in general ten thousand years or older, whereas the pseudomorphs on the jade surface are at the most 6 thousand years old.

The chemical weathering process continues to take place within the surface micropores and microcracks of the jade surface, producing a ferruginous gel-like substance that eventually spills onto the jade surface, forming a thin semi-transparent crust. Such crust is hard to discern under the microscope unless the semitransparent crust is cracked, as on this Liangzhu (3400-2250 BC) disc with three birds (Figure 39).The

crack becomes apparent when the disc is examined under the microscope ( Figure 40). A

small piece of the crust is lost, exposing the undersurface of the disc seen in the area within the red circle and on further magnification (Figure 41). The defect on the crust

can now be seen, providing proof that such a crust exists. The ferruginous substance can thicken into a plaque on the jade surface. Figure 42 is another magnification view of figure 26, the C – dragon pig dragon. Amid greyish-yellow phyllosilicate crystals is a clear

plaque with an edge adjoining the clay phyllosilicate. At the center of the plaque, are silvery metal granules forming a straight line, identified within two red arrows. The presence of these metallic granules affirms the plaque is ferruginous. The color and the semi-transparency of the plaque are frequently mistaken as the jade surface looking at it with naked eyes and widely simulated by fake jade makers by covering part of the fake jade with dye and other parts without. Seeing such a pattern of an exposed jade surface can be a clue of forgeries.

The presence of the weathering crust on the jade surface is a good indication that the jade piece is genuine. This thin crust is only about 0.1 to 0.2 mm in thickness, comprising of clay phyllosilicate and iron oxide minerals. Many geochemical changes can be observed on this thin crust. Figure 43 is a Hongshan pig dragon beast. On it is a

group of brownish granules within the semitransparent crust (Figure 44). Such granules

black or deep brown in color and often referred to as charcoal, are Hematite inclusions formed inside the ferruginous gel. Hematite can also be reddish-brown. When it forms as a crust, it creates an optical illusion that the jade piece is reddish-brown in color, as we have already seen on the zoomorphic beast in figure 23. Figure 45 is a Han beast disc. A

magnified oblique view reveal the coloring is due to surface Hematite encrusting (Figure 46). Iron oxide encrusting is a frequent finding in Hongshan jades, as on this Hongshan

zoomorphic insect beast (Figure 47). Again, to appreciate the presence of the crust, an

oblique view under the microscope is essential (Figure 48). The different colors on the

jade surface is due to the different mineral formed. The red and black are from iron oxides, and the greyish white is from the clay minerals. Figure 49 is another view of figure 47, the zoomorphic insect beast. The crust essentially becomes the jade surface

taking on the color of the secondary products as well as defects like the cracks that are in the crust rather than in the jade (Figure 49). Weathering product iron oxide in the crust can result in various colors of the Hongshan jade. The color change on the Hongshan eagle in figure 50, is likely from Goethite, as also likely the Hongshan bird zoomorphic in

figure 51 that has a distinct crystal formation (Figure 52a). Figure 52b is an oblique view

of the jade surface. The iron oxide crystals are clearly on the surface of the jade piece. The beautiful color on the Neolithic disc on the cover of Jessica Rawson’s book, “Chinese Jade, from the Neolithic to the Qing” is not a natural color. The color is from the iron oxide formed on the jade surface similar to on the zoomorphic bird in figure 52.

There is a mineral formation unique to Hongshan jade. Figure 53 is a

Hongshan bird with a worm on its head. The unique mineral finding is inside the drill hole as in figure 54. The pin-like crystal is an iron oxide, most likely Goethite. Drill holes

preserve water and have a cave-like environment suitable for mineral development. This phenomenon is rarely seen as such mineral formation is uncommon. Although fragments of this type of mineral can be found inside other drill holes, a fully developed formation can only be found in one other Hongshan Jade, a zoomorphic with a beard (Figure 55). Inside its two obliquely drilled holes on its back are multiple of such mineral formations( Figure 56).

The key to distinguishing a genuine buried nephrite from forgeries is to recognize the color change on the jade surface comes from the secondary weathering products, clay minerals, and iron oxides. Only when the secondary product crystals are seen on the surface, authenticity can be ensured.

Through Jade to Hongshan cultural beliefs

Throughout Chinese history, jade has been regarded as a stone with mysterious power, a belief especially true during the Neolithic period, and hence jade was exclusively the medium for expressing religious beliefs. As with any art form, such expression reflects the thinking of the carver. Through jade, the carver presents his thought and outlook of his world and his perception of beauty to the viewers. With the Hongshan culture leaving no written record, jade provides a path for a glimpse of the thinking and the religious beliefs of the culture. Artistically, Hongshan jade, even with all the limits of being a Neolithic culture, attains a high artistic level, not less than any subsequent Chinese culture periods, thousands of years after.

The majority of the Hongshan jades are small, measured 3 to 8 centimeters. Most of the small piece has hanging holes like those discussed in the drill mark section above, indicating that such small pieces are for hanging on the body. None of the large pieces, which can measure up to eighteen centimeters, has hanging holes, except the hook cloud plaque (Figure 57), that can measure to 23 centimeters. With drilled holes on

top and to the sides, the Hook Cloud plaque most likely was for hanging on the human body. Some speculation that the plaque is an abstraction for a religious belief. Other large pieces longer than 15 centimeters like the zoomorphic beast in figure 35, and the zoomorphic insect beast in figure 47, as a rule, do not have drill holes as they probably are statues rather than a hanging piece.

Most of the Hongshan jades are beasts with human characteristics, a form of zoomorphic. These beasts zoomorphic intermingle with birds and insects often on top of the head of the beast. The pig dragons and C-dragons are a class of its own. Chinese scholars believe they are the forerunners of the Chinese dragon. Their faces, however, resemble that of a Hongshan beast (Figures 58 and figures 9a and b). The pig dragon is

more versatile and often combines with another subject, as with the C-dragon in figure 26. More often, the pig dragon combines with the zoomorphic beast (Figure 43), and in figure 58, in semi human form with a pair of human legs. A more complex pig dragon is in figure 59, one with a zoomorphic beast head, losing the characteristic pig dragon eyes connected with a pair of lines, and a pair of insect or bird wings. Both pig dragons in figure 58 and 59 give an impression that the pig dragon can evolve into other forms. In

another word, it is a therianthrope rather than a zoomorphic. It is quite often that the Hongshan animal and beast, as the pig dragon in figure 59, take more than one form. In figure 47, the zoomorphic beast is also part insect, and in figure 55, the zoomorphic beast is part bird and part insect. The combination forms may mean the Hongshan beast, man, insect, and bird can evolve into each other and are more likely therianthropes.

The Hongshan beasts and animals are not necessary a zoomorphic with more than one entity in one form but can occur as two different individuals. Figure 60 is a pig

dragon on top of a beast, and figure 61 is a beast on top of a pig dragon. Notice both the

pig dragon and the beast in figure 60 are facing the same direction, and the beast and the pig dragon in figure 61 are facing the opposite direction. Direction pointing is often a theme in the Hongshan culture, as we have seen on the ox nose part of the through and through drill holes on the C-dragon (Figures 8 and 9). Figure 62 is a beast. On its back is

an owl facing opposite to the beast, resulting in both the beast and the owl showing the front (Figure 63). The beast zoomorphic in figure 64 also has an owl on its back. But in

this case, it is the owl’s back we are seeing as the beast and owl are facing the same direction (Figure 65). Figure 66a and b is a bird standing facing forward on top of a zoomorphic beast. This statue was a pair. Unfortunately, figure 66 is the only one in my

collection. The other statue, the bird on top of the zoomorphic beast, faces backward. The theme of direction pointing, at a time in the same direction, and in others in a direct opposite is consistent in Hongshan jades. These Hongshan jade carvings illustrate clearly the concept of the same and opposite in the form of direction, as we shall see later also in the form of the two different sexes.

The goddess temple and the six pregnant female clay figurines excavated from the Hongshan archeologic site lead to the belief that Hongshan is a fertility worship culture. Hongshan is also the only Chinese culture period that displays the female figure in their jade art by carving breasts on the female characters, as on the female bird

zoomorphic (Figure 67), and the two female beasts zoomorphic (Figures 68 and 69). All female characters have round eyes and all female beasts zoomorphic sit in a semi kneeling position on their legs. This sitting position is like that of the later Shang and Zhou period, tracing back a long tradition. The male counterpart has almond-shaped eyes, and most of the male beast squats (Figure 70), with less often sits on the ground (Figure 71). Both the male and female may stand. Notice also are the two different types

of horns on the female zoomorphic in figure 68 and the male zoomorphic in figure 70. It is possible that these are not horns of the beasts, but headgears or even hairstyle of the Hongshan period. The shape of the eyes differs between males and females with female eyes round, and the male eyes almond-shaped, provides clear identification of gender in human, beast, bird, or insect. Most birds have round eyes. The almond-shaped eyes on the bird in figure 72 distinct him as a male, a contrast to the round eye bird in figure 53,

the female bird zoomorphic in figure 67, and the female beast in figure 68. Males and females are often in pairs, and when they are in pair, each faces a different direction. Figure 73 is a pair of males and female zoomorphic beasts with each facing an opposite

direction. The two zoomorphic beasts of opposite sexes in figure 74 facing up and down. Figure 75 is a pair of bird beast zoomorphic, back to back in two directions with the smaller round eye female on the back of the bigger almond eye male. The opposite position emphasizes the contrast of male and female consistent with the opposite directions indicated by the ox nose on the C-dragons, and the opposite directions facing by the zoomorphic, birds and beasts. What it shows is the idea of opposing directions of front and back, forward and backward, up and down, female and male, are in one, a philosophy that may well be the embryonic beginning of Yin and Yang.

Pregnancy is a theme in the Hongshan religious belief. From the excavation of the Hongshan archeology site, there are six pregnant female figurines. Such theme of pregnancy also reflects in the jade carving. Figure 76 is a pregnant beast zoomorphic.

Unfortunately, none of the figurines retains the head. Having human-like breasts in these figurines may not mean they are human, as seen in figure 67, the female bird zoomorphic also have human-like breasts and a bird head. The zoomorphic in figure 76 has a protruding abdomen indicating pregnancy. The head of the beast has a C-dragon crown and a pair of two lines connected eyes. A connection of eyes in such a manner is only in the pig dragon. The combination brings in the importance of the C-dragon and the pig dragon in relation to life. Such a combination also confirms that the beast is a therianthrope as it shows more of a change from the human, beast, to C-dragon and pig dragon as opposite to a zoomorphic, a human in beast form.

A unique bottomless tube (Figure 1) thought to be religion related is also a subject of the jade carvings. Figure 77a and b is a turtle climbing up such a bottomless tube, and figure

78 shows a bottomless tube on the feet of a bird zoomorphic. The association of the bottomless tube, the turtle, and the bird zoomorphic may indicate the Hongshan

religious belief is related to nature, an interrelationship between humans and birds, insects, and beast. Both the bottomless tube and the jades are found only in graves, making such a relationship likely an afterlife belief.

Often found in Hongshan carved nephrites are insects, birds, and beasts on top of a larger beast zoomorphic. Figure 79 a and b is a beast zoomorphic with two

winged insects on its head. The eyes of the insects become the beast zoomorphic eyes. Figure 80 a and b is a small beast on top of a larger beast zoomorphic. Figure 81 a and b

is a bird on a beast zoomorphic, and figure 82 a and b is a double-headed beast on a larger beast zoomorphic. These carvings further demonstrate the close interrelationship

between human, beast, bird, and insect in the Hongshan belief. All the zoomorphic with an insect, bird, or a small beast on their head have almond shaped eyes indicating they are male beasts. The eyes of the beast zoomorphic in figure 79 are the eyes of the insects. But the squatting position tells that the beast is a male. There are also carvings with a human face. Figure 83 a and b is a man’s face and figure 84 a and b is a man’s face with two legs attached to it. Both have a winged insect on top of their heads. The similarity in

position, as well as the similarity of the insects on their heads, may indicate the male beast zoomorphic and man are interchangeable and identical. The meaning of the insect, bird, and beast on the heads of man and beast cannot be known. But that it only associates with males indicates male is a special class. Only other human face on the carvings is this female beast zoomorphic with a human face mask behind her head (figure 85 a, and b). No insect, bird, or beast appears on the head of the female zoomorphic, a distinct difference from the male counterpart.

Hongshan was a Neolithic culture 6,000 years ago. To many people today, the culture was primitive. Such an assumption is reflected in people who carve forgeries, creating jade pieces they believe primitive and call them Hongshan jade. Without the opportunity to see an authentic Hongshan jade artifact, the fake jade carvers produce inferior objects out of their imagination of what they believe a Neolithic primitive culture artifact. Such imagery permeates Chinese society today. Yet the Neolithic people of Hongshan carved out jade pieces that are both technically and artistically advance even in today’s standard. The technique they used was principally grinding with abrasive, leaving behind a smooth jade surface with minimal tool marks. The most frequently found tool marks are inside drill holes. Drill holes are made with bone drills and abrasives, leaving behind shallow, irregular and circular marks on the side of the drill hole (see figure 13). Most of the Hongshan jades are round three dimensional. Without the benefit of today’s instruments, the Hongshan carvers were able to carve zoomorphic beasts squatting on their two feet, essentially putting the center of gravity of the mass onto two small points ( figures 32, 37,80 and 84), something that today’s fake jade carvers cannot achieve. Most of the jades are superb artistically. Consider the beautiful geometric curve of the C-dragon (figure 9), the line management of the female beast (figure 22), the imaginative birdman (figure 51), and the balance in the abstraction of the hook cloud plaque (figure57). One can go on and on. If one cannot see artistic beauty in a Hongshan jade piece, one can very much doubt the authenticity of it.

Using abrasive has always been the foundation of jade carving in China. From the Neolithic time to the Zhou Dynasty, the technique was grinding with the use of abrasive, a tedious and time-consuming process, but left behind a smooth jade surface with little to no tool mark. During the Han Dynasty, latches came into use also working with abrasive. Jade carving became more efficient, required far less time to accomplish, but also left behind distinctive tool marks. Such a technique very much continues to the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912) resulting in tool mark similarity between the jade made before Han and after Han.

Jade of each period and dynasty has different style and characteristic. Hongshan jades are of no exception. Hongshan carvers often combine two characters into one piece, a form that has not seen in any period of Chinese jade. Such a combination often presented creatively. Figures 86 a, b, and c show a beast combining with a cicada. The front is the beast, the back the cicada and with the bottom the cicada

face. Hongshan carvers also have a sense of humor. Figure 87 a, b, and c is a piece that looking at it from one side is a face (figure 87a). Turn the piece around, and there is another face (figure 87 b). The back side is a frog on a leaf (figure 87 c). The Hongshan

jade is genuinely an art form in no sense inferior to any other period. Notice the crack line on figure 87a. The crack line is curved an indication the crack is on the secondary weathering chemical. If it is on the jade itself, it will be straight due to the structure of the nephrite crystals. Also, notice the similarity between the human face in figure 87a and the cicada face in figure 86c, consistent with the Hongshan theme of interchangeability and intermigration between humans and animals.

From Hongshan to Han

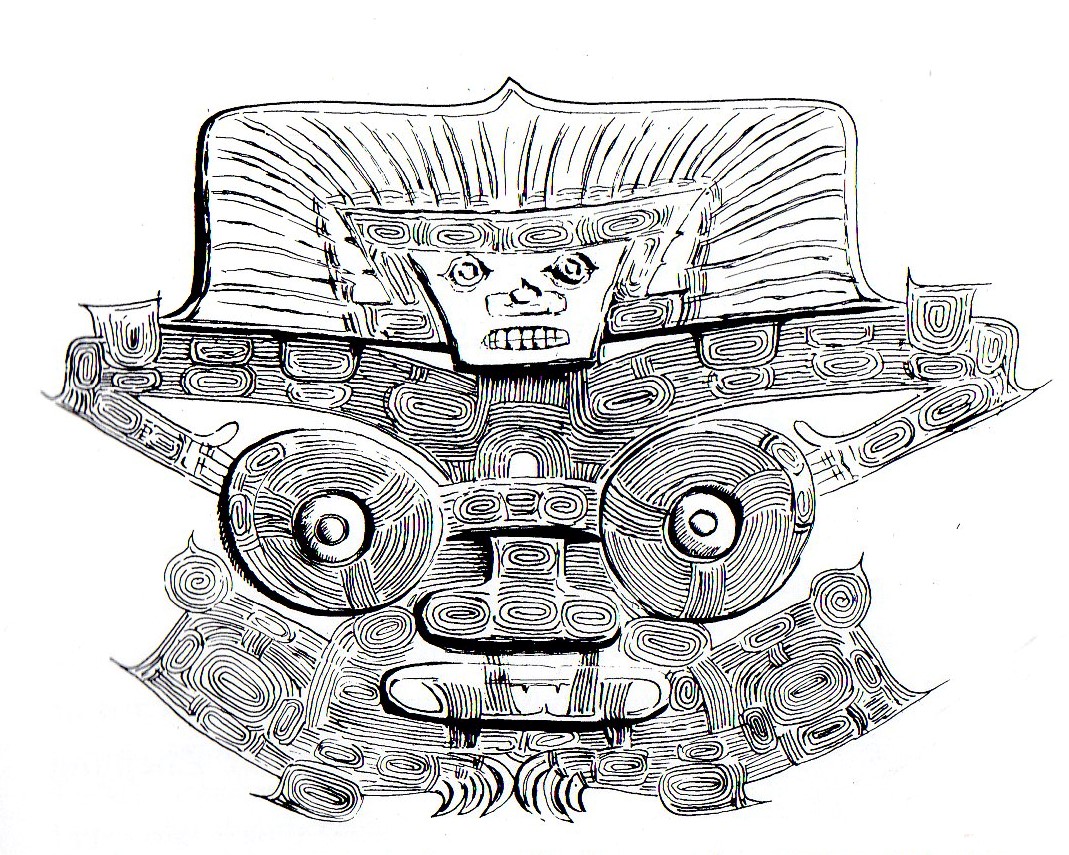

One of the mysteries in Chinese antiquity is the meaning of a beast face that appeared on the Shang (1600 BCE – 1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046 BCE – 256 BCE) bronze ceremonial wares (Figure 88). The beast face also appears on a Shang jade vase (Figure 89 a and b). The origin or the meaning of such a beast face has led to many speculations

with no answer for certain. Tracing back, the only resemblance of the Shang beast face is the face of the Hongshan zoomorphic beast. The question is that can the Shang beast face has an origin in the Hongshan beast zoomorphic. Figure 90 is the face of the Hongshan zoomorphic beast with a bird on his head (Figure 66a and b) and look again at figure 86a

the beast face in front of the cicada. Figure 91 is the Hongshan zoomorphic beast in front of the hook cloud plaque in figure 14. The hook cloud plaque is an abstraction that has a

ligious meaning. The presence of it behind the zoomorphic beast gives the zoomorphic beast a religious significance. When comparing the three Hongshan beast faces, figures 86a, 90 and 91, to the Shang bronze and jade vase beast faces in figures 88 and 89, the similarity between all these faces is there, making it very likely that the Shang beast face has an origin in the Hongshan zoomorphic beast.

But if that is the case, why did the people of Shang carve the Hongshan zoomorphic beast face onto their ceremonial bronze wares. The answer lies in two Liangzhu culture (3400 BCE – 2250 BCE) jade butterfly plaques (figure 92 and figure 93).

Liangzhu is another Neolithic jade culture in China, overlapping in time with Hongshan (4700 – 2900 BC), coexisting at the same time for five hundred years. Physically they were a thousand miles apart. The Liangzhu culture has three images carved on their jades, the godman 神人 (figure 94), and the two god beasts 神獸 seen in figure 92. The godman is the ancestor king, and the two misnomer god beasts are symbols of human representing the

present living king and the ancestor king. The lower god beast with a nose in figure 92 is the symbol of the ancestor king and therefore is carved on the body of the godman, the ancestor king, in figure 94. The upper god beast without a nose in figure 92 is the symbol of the present living king, and therefore is carved on the cones, axes and beads, personal belongings of the current living king. (The explanations of the godman and god beasts are found in the blog post “良渚神人神獸的意義及其宗教中心思想,” in this web site). Except for the one on the lower part of the butterfly plaque in figure 93. the Liangzhu culture has never carved the beast face on their jades. This beast face is the first-ever beast face in Chinese history, predating the Shang (1600 BCE – 1046 BCE) by at least one thousand years. As the beast face is not part of the Liangzhu culture, there must be a base for this beast face carving, and the only possible source is the Hongshan zoomorphic beast. In figure 92, the Liangzhu god beast with a nose occupies the lower position of the butterfly plaque. In figure 93, that position is replaced by the beast face. Since the Liangzhu god beast with a nose is the symbol of the ancestor king, the replacement of it with the beast face indicates the beast face carries the same meaning, that It is also a symbol of the ancestor king. The Shang ceremony is to worship and honor the ancestor kings. It is, therefore, logical to have the beast face, a symbol of the ancestor king carved on the ceremonial bronzes.

Since the Neolithic time, in the subsequent periods in Chinese art, the beast face is not as frequently seen on the jades as on the bronze. It appears on a Zhou Dynasty disc as abstract designs (figure 95). It also appears on a seal (figures 96a and b). This seal

has a beast knob, and on the four sides, four beast faces. Four characters are on the seal surface 黃漢起印. The name indicates that it is the seal of a general 黃蓋in Han of the Three Kingdoms period (220 -280 AD). After Han, the beast face is no longer seen in China. The disappearance has to do with the tremendous change in Chinese culture after Han. Both the bird and the beast face represent the ancestor king, with the beast face as the symbol, and the bird believed to be the medium of the ancestor king’s soul when he makes his journey to the sun (explanation in “渚神人神獸的義及其宗教中心思想”). Such religious belief is the reason why both the beast face and the bird are on the ceremonial bronze and the Shang jade vase (figure 89a). After the Han Dynasty, Buddhism came to China. Buddhism replaced the original religious belief of ancestor king worship and with it the ancestor king symbol of the beast face and the bird. Yet ancestor worship remains in Chinese society even today. The Hongshan and Liangzhu spirit are still deep in Chinese culture.

Hongshan religious beliefs

The Hongshan jades present a pattern through which it opens a path to the thinking and beliefs of the carvers. The finding of the goddess’s head and the pregnant female figurines at the temple site show Hongshan was a fertility worship culture. This belief is also reflected in jade in the pregnant therianthrope (figure 76). The bottomless clay tube thought to be of religious significance is also found in the jade carving (figures 77 and 78). Jades are buried in graves and should express the religious belief of the afterlife apart from the fertility worship associated with the temple. Often the jade carvings are zoomorphic beasts, semi-human, with birds and insects. Some combine more than one as if it is in transformation, a therianthrope rather than a zoomorphic (Figure 59). Such a transformation afterlife may indicate the Hongshan belief in reincarnation or transmigration after death. Reincarnation or transmigration is a universal human belief shared by people in India, ancient Greek and, Rome, natives in North America and Australia. That this is may also a belief in the Hongshan culture should not be a surprise.

The Hongshan zoomorphic beast, birds and insects, all show a clear distinction between males and females, with males have almond-shaped eyes and females have round eyes. Male and female are often set in one piece facing the opposite direction (figures 73, 74, and 75). The concept of opposing directions and yet form as one is also shown by the ox nose part of the round drill holes on the C-dragons and the opposing direction facing by the zoomorphic beasts and birds on the same jade piece ( figures 63, 64 and 65). This thinking, together with the male and female opposing but complement each other into one piece, is very much in line with the Yin and Yang philosophy that comes later into the Chinese culture.

Hongshan jade also gives us a glimpse into a Neolithic society, a society with men and women playing different roles, the males into the position of kings, and females into the role of fertility. The beast zoomorphic in the Hongshan culture and the godman, god beasts in the Liangzhu culture, all represent ancestor kings’ worship that passed on to the Shang Dynasty and influences the Chinese culture even today.

Ls,

After reading your articles I found out more about jade and learned a lot about the weathering process itself. By saying so, I see some some similarities with my ancient chinese jade objects. I am very interested in your opinion about these objects. Is it possible to send some pictures so you can do the judge?

Thanks in advance

Robby

LikeLike

Thank you for your visit. If you wish you can come back to visit my site. My new blog is : The evolution of Chinese jade making from the Neolithic to Han, The griffin winged beast and the Eurasia Stepp connection, and Jades of the Tang Dynasty. You will see more tool marks and weathering product. Go back to nephritejade-radixcultira. com and click on the menu and you will see all posts.

LikeLike

Thank you for these insights!

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment and visit. If you wish, you can come back and visit the site. My new blog is “ The evolution of Chinese jade making from Neolithic to Han, The griffin winged beast and the Eurasia Stepp connection, and jades of the Tang Dynasty”. Go back to nephritejade-radixcultura. com and click on the menu. All posts will come out. Thank you again.

LikeLike

I read with interest. The faint metallic granule lines found on the surface of sculptures are tool marks from metal implements. Generally any artifact or stone sculpture gains these lines when handled by people wearing rings, during excavation using picks etc., or when carried in a pocket with a coin or knife.

LikeLike

Sorry for the late reply. These faint metallic lines are not random as metal markings are. They are metallic granules in a line and often line up at the ecge of the phyllosillicate crystal. They only reflect light at a specific angle, the reson why you cannot see them unless you flip and tilt the jade surface underneath the microscope to the right angle, a phenomemum known as birefringence. The granules are from the ferogenous gel from the weathering. I have to be frank with you that I do not fully understand the phenomemum. I can recommend you to read the article by MICHAEL ANTHONY VELBEL: WEATHERING OF HORNBLENDE TO FERRUGINOUS PRODUCTS BY A DISSOLUTION-REPRECIPITATION MECHANISM: PETROGRAPHY AND STOICHIOMETRY. ; Clays and Clay Minerals, Vol. 37, No. 6, 515-524, 1989.

LikeLike

Hello, this is a great site, so informative. I have many jade carvings, some I believe to be to be ancient, but I wonder if you would be kind enough to recommend to whom I can have them looked at to determine authenticity? Thank you

LikeLike

Sorry for the late reply. Authentication is notorious in Chinese nephrite. This is what these writings are about. Find a microscope and look at them youself. But as I have always said, Everyone is an expert in Chinese nephrite authentication. When someone present you with a piece to authenticate. All you need to say is that it is a fake, and you are right 99.99% of the time.

LikeLike

I’m late to this party.. I’ve been enamored by the Hongshan style since I first learned about them in 2019. There is no other art style quite like theirs, and it was amazing to learn more- in an easy to understand way, about authentication and general meaning behind the symbolism. All of what I’ve collected, I’ve known for years is fake or repro- and I’ll never be able to afford something authentic. But as an artist, I still adore the representations I have, and will continue to collect and wear representations of the style, now with much more awareness of what symbolism to look for in a more accurate representation of their work and beliefs. Thank you for this easy to understand article, with beautiful clear photos.

LikeLike

The Hongshan culture has a few very similar imagery to the Aztec culture

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. I do not know what you mean there are similar Aztec Images to the Hongshan culture. If you mean there are similarities between the two cultures I have to disagree. Many people in China still believe that the Mesoamerican culture is influenced by ancient Chinese culture. I have not seen any connection at all. One often cited reason is that both cultures have jade. Looking closely at the Mesoamerican jadeite statue I have and comparing it to the Chinese nephrite, the carving technique used by both cultures are clearly completely different. Jade is not the same jade.

LikeLike